Anatomy lesson

Your core musculature is comprised of far more than the visible "six-pack" muscles typically associated with core strength. In this lesson, you’ll learn about the different muscles that are vital to building a strong, supportive core.

Illustration: Bonnie Hofkin

Illustration: Bonnie Hofkin

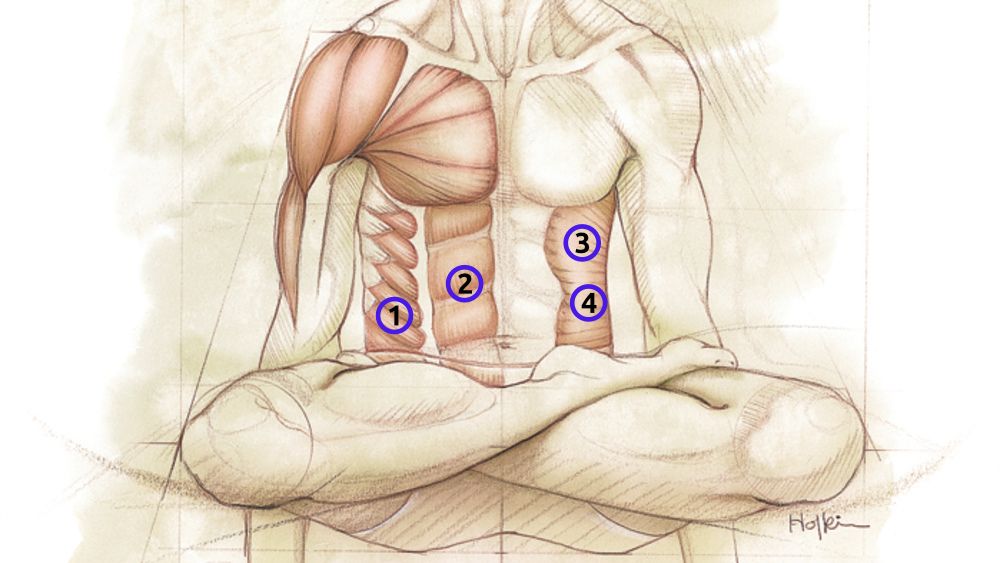

1 - External Obliques

Part of the outermost layer of abdominal muscles, the external obliques start at the side and front body at the ribs and sternum and wrap around the front torso to the back of your pelvis. They work in concert with the internal obliques, rotating the trunk and flexing it diagonally, and join with the rectus abdominis to add power to your forward bending. The obliques have a protective function in twisting: They ensure that the spine twists evenly, so that the vertebrae do not turn too strongly in any one place and injure an intervertebral disk.

2 - Rectus abdominis

The most external of the core muscles, the rectus abdominis runs vertically from the middle of the rib cage in the front of the body to the pubic bone and is associated with “six-pack abs.” It’s worked strongly in poses such as Half Boat Pose (Ardha Navasana) and arm balances such as Crane Pose (Bakasana). Rectus abdominis does make your belly look trimmer by providing support for your abdominal organs, and its active function is to bend the spine forward.

3 - Internal Obliques

The internal obliques lie underneath the external obliques. The two internal obliques, left and right, originate primarily from the pelvis and travel diagonally up across the abdomen. All of the obliques cross the abdomen diagonally like a supporting girdle, and have upper fibers that attach to the lower ribs and can restrict rib cage movement.

4 - Transversus abdominis

The deepest layer of abdominal muscle, the transversus abdominis is located beneath the internal obliques and wraps around much of your lower torso like a corset, supporting the internal organs and stabilizing the torso. One of the few muscles with fibers that run from side to side, it’s very important both as a support muscle and as an accessory muscle in breathing. You flex this muscle to pull in your belly.

Illustration: Bonnie Hofkin

Illustration: Bonnie Hofkin

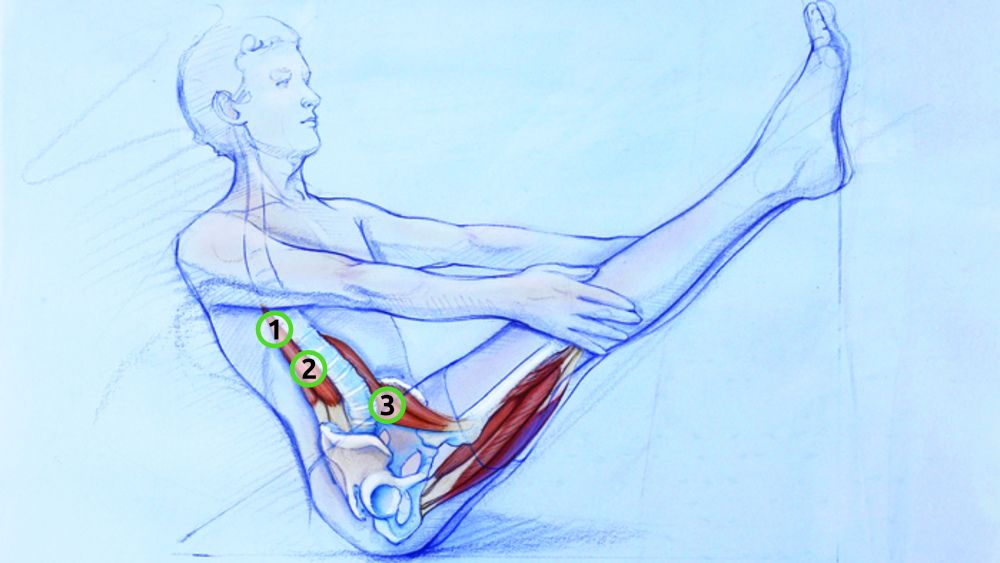

1 - Multifidi

The multifidi is actually a series of two groups of small muscles along the spinal column, beneath the erector spinae, that connect each vertebra to the ones next to it and give the spine support: The superficial group helps keep the spine straight, while the deeper muscle group offers stability. These muscles are recruited during many core actions—bending backwards and sideways—to prepare the spine for movement and prevent injury. They can be hard to isolate; to feel them engage, try co-contracting them with the pelvic floor.

2 - Erector spinae

These long muscles run vertically up the spine and rib cage from the pelvis and sacrum to the neck and head. They help you keep a long, straight torso by working to oppose the action of the abdominal muscles (the rectus and transversus abdominis and obliques), which flex the spine and pull the pubic bones and the front of the rib cage closer together.

3 - Psoas

The psoas is the deepest and one of the largest muscles in the body. On each side of your lumbar spine, it attaches to the vertebrae and stretches over the hip joint to attach at your femur (inner thigh). You use the psoas when you walk; it also plays a critical role in forward bends, working to help flex your spine. Especially important, the psoas provides structural support for the curves of your spine. In fact, it runs so deep that when you’re lying down, your abdominal organs literally sit on top of it, which is why the psoas can have a profound effect on the appearance of your abdomen.

Illustration: Bonnie Hofkin

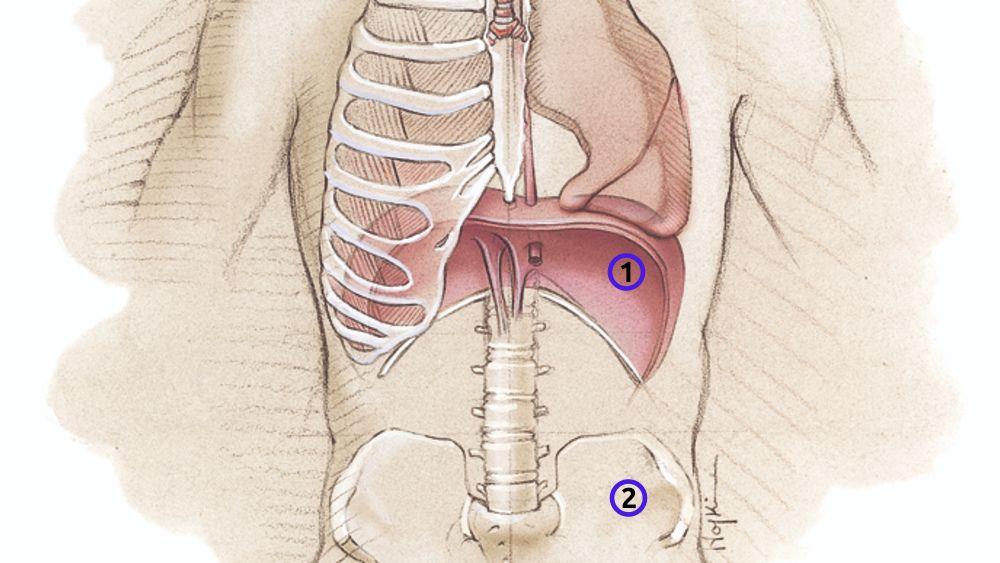

1 - Diaphragm

The diaphragm muscle stretches like a drumhead across the bottom of the chest, separating the heart and lungs above it from the abdominal cavity and digestive organs below. When relaxed, the diaphragm curves upward like a dome. When it contracts, it shortens and flattens, pushing on the digestive organs below and lengthening the chest cavity above. This expansion of the chest cavity draws air into the lungs—the lungs have no capacity to expand or contract on their own. The diaphragm also works in combination with the transversus abdominis and pelvic-floor muscles to pressurize your torso, protecting your spine from stressful loads.

2 - Pelvic floor

Your core musculature actually starts here at the pelvic floor, the complex triangular mesh of muscles situated under the pelvis, connecting the tailbone to the pubic bone. There are actually 16 muscles in the pelvic floor, but from a day-to-day functional standpoint, they’re at their best when working in concert, so it’s easier to think of them as a single unit. If you think of your core as a ball with air in it, your pelvic floor forms the bottom of the ball, the diaphragm the top, and the abdominal muscles wrap around the center, and they all work together to support your lumbar spine.

Illustration: Bonnie Hofkin

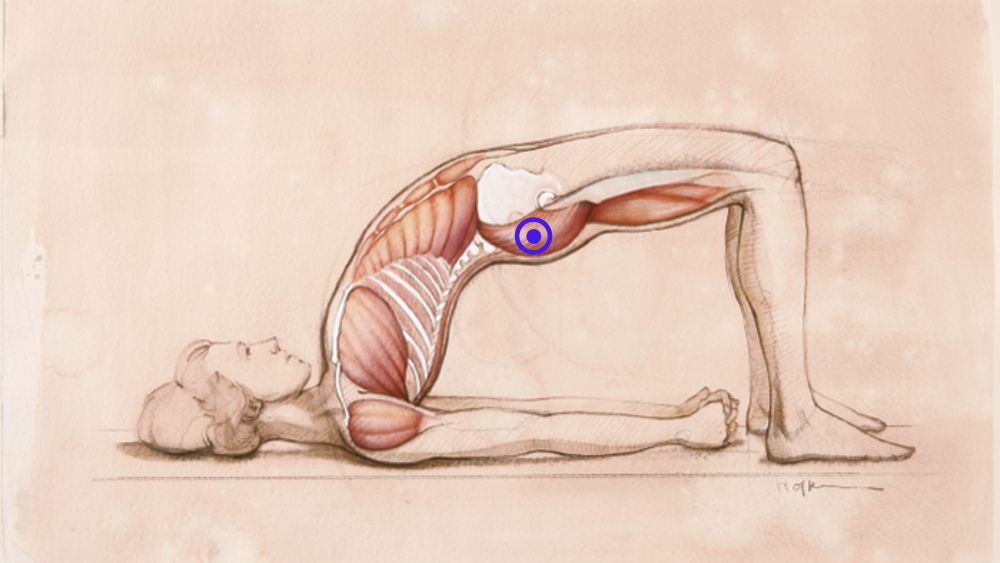

Gluteus maximus

The gluteus maximus is the largest of the three glute muscles. It originates on the sacrum at the base of the spine and nearby pelvis, and then runs diagonally down and across the buttocks to insert on the outer upper femur (thighbone). The gluteus maximus contracts when you stand up; it also works to support upright, standing postures. If the gluteus maximus is weak, muscles along the lower spine, in addition to the hamstrings, will often overcompensate, potentially causing back tension and spinal misalignment. Plus, weak gluteus maximus muscles can mean a too-tight pelvic floor and too-tight groins.